The Rustic Style in Canada's National Parks

As part of Parks Canada's centennial celebrations, the

Canadian Register of Historic Places (CRHP) is pleased to celebrate

the centennial by presenting articles relating to past achievements

at Parks Canada, and to convey to Canadians the important

leadership role it plays in the conservation of natural and

cultural heritage across the country. The theme for July is

National Parks and therefore the focus of this article is the

picturesque Rustic architecture that emerged as a style for

recreational and administrative buildings within the National

Parks. The buildings featured in this article are designated

federal heritage buildings and/or National Historic Sites.

More information on these buildings is available on the

CRHP.

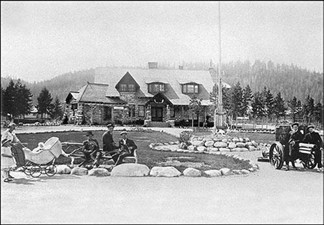

Balancing the romance of the Canadian wilderness with the

amenities of modern living, the visually distinctive Rustic style

architecture in the National Parks is an attractive building form

closely associated with recreational areas in Canada. Rustic style

architecture covers a wide range of structures and construction

methods. From its Romantic roots in the backwoods of Canada, the

Rustic style emerged as a building style in the National Parks soon

after our first protected area, Banff National Park, was

established in 1885.

The Rustic style's roots stem from the simple log buildings

constructed by trappers, railway workers and prospectors. Often

reminiscent of the log structures of early settlers, the Rustic

style was an appropriate style sympathetic to the wilderness

setting of the National Parks remote environment. In Canada, Rustic

style log bathhouses and CPR stations at Banff were first

constructed between 1886 and 1888. George Stewart, the park's first

superintendent, introduced the Rustic style to Banff, which he

thought most appropriate for the natural surroundings. In

time, this style was adopted by the National Parks system in order

to project a distinctive image associated with new parks.

What were the origins of this distinct style? There were many.

It was partly influenced by traditional Swiss chalets that had been

introduced to North America by Andrew Jackson Downing in the 1850s.

Log construction techniques had been popularized by French

architect Calvert Vaux, in his 1857 pattern book Villas and

Cottages. An embrace of folk architecture by architects

also influenced the style. These influences remained as

Rustic style architecture developed in the late 19th

century. It manifested itself in the National Parks in the form of

vernacular log structures with shingles, prominent rough stonework,

deep eaves, rough board siding and verandahs, and also as a

deliberate Swiss quality, supported by rectilinear or diagonal

bracing with deep eaves, was part of a conscious effort to promote

tourism.

When first designated as

National Parks, the lands often contained no permanent settlements.

Increased tourism ushered in roads and recreational facilities that

transformed the National Parks into destinations for tourists in

automobiles. In 1909, a full-time warden system began, and after

1918, more wardens' cabins were prepared to standard plans. These

usually small, one-room structures were sometimes adapted for

permanent occupancy. Patrolling wardens used cabins for overnight

accommodation along patrol trails established to enforce

regulations within the park boundaries. Constructed from locally

cut logs, these structures varied in size, proportion, corner

notching, window and door displacement, and in their verandah

support systems. The standard plan included a six-foot verandah

roof overhang supported by the roof purlins, which was often

modified by decorative supports. Examples of the type are Hoodoo Warden Cabin and Topaz Warden Patrol Cabin both in Jasper

National Park of Canada. The National Park Warden Service

constructed Warden's Cabins, fire towers, cabins, stables, and

sheds for patrol purposes, often in a Rustic style. This network of

service structures expanded over the years as the parks developed,

enabling the enforcement of wildlife and forest protection

regulations, and the control of tourism in Canada's National Parks.

These modest and functional buildings were by no means impressive

compared to the more substantial Rustic buildings in the National

Parks' townsites.

When first designated as

National Parks, the lands often contained no permanent settlements.

Increased tourism ushered in roads and recreational facilities that

transformed the National Parks into destinations for tourists in

automobiles. In 1909, a full-time warden system began, and after

1918, more wardens' cabins were prepared to standard plans. These

usually small, one-room structures were sometimes adapted for

permanent occupancy. Patrolling wardens used cabins for overnight

accommodation along patrol trails established to enforce

regulations within the park boundaries. Constructed from locally

cut logs, these structures varied in size, proportion, corner

notching, window and door displacement, and in their verandah

support systems. The standard plan included a six-foot verandah

roof overhang supported by the roof purlins, which was often

modified by decorative supports. Examples of the type are Hoodoo Warden Cabin and Topaz Warden Patrol Cabin both in Jasper

National Park of Canada. The National Park Warden Service

constructed Warden's Cabins, fire towers, cabins, stables, and

sheds for patrol purposes, often in a Rustic style. This network of

service structures expanded over the years as the parks developed,

enabling the enforcement of wildlife and forest protection

regulations, and the control of tourism in Canada's National Parks.

These modest and functional buildings were by no means impressive

compared to the more substantial Rustic buildings in the National

Parks' townsites.

Often designed by architects, there are many distinctive Rustic

style buildings, such as the Banff Natural History Museum, Twin Falls Tea House, and Cave and Basin Hot Springs. Commercial

operators at resorts in the National Parks also used the Rustic

style. Hotels, motels, and lodges embraced it; garages,

restaurants, police stations, fire departments, tearooms and

railway stations equally adopted the style. Most of the

government-owned buildings, including picnic shelters, bandstands

and parks administration buildings, were designed in this style. It

was especially popular with the development of tourism, outdoor

recreation, public and private ownership in parks and federal

make-work projects during the Great Depression.

The popularity of the Rustic style was due to its apparent

informality. Parks staff even built two log cabins to accommodate

Archibald Belaney, popularily known as "Grey Owl" and his wife

Anahareo. Grey Owl, a noted author and advocate of the

wilderness, worked for the parks service as a naturalist. In 1931,

Grey Owl and Anahareo occupied a log cabin in Riding Mountain National Park, and

in 1932, they resettled at Ajawaan Lake in Prince Albert National

Park.

Many of the wide ranging Rustic themes were first seen on

tourist accommodation in the parks, which include Bungalow camps,

townsite lodges, and resort hotel complexes. Examples include the

log cabins provided as rest houses for Trail Riders of the Canadian

Rockies, an organization founded by the Canadian Pacific Railway

(CPR) in the 1920s to provide horse riding through the park.

Another example is the two-story tea house used as a stopping place on a busy

hiking trail in Yoho National Park of Canada. Tea houses also

provided meals and shelter for hikers and trail riders taking back

country excursions near the railway's network of hotels and

bungalow camps.

The Canadian Pacific Railway, actively involved with tourism

throughout the Rockies, promoted hiking and climbing and brought

Swiss guides to Canada to lead climbing parties. Several buildings

were constructed to support hikers and climbers of the Alpine Club

of Canada. High altitude stone shelters, similar to

those found in the Alps, were provided to accommodate climbing

groups led by Swiss guides. Abbot Pass Refuge Cabin is perhaps the best

example constructed of split stone at an altitude of 9,585

feet.

Though coming from humble roots, the Rustic style became much

more refined and sophisticated. For example, the Banff Museum (1902-03) is a distinctive

two-storey wood-frame building designed in a rustic Swiss style

with a decorative crossed-log wall pattern, and is perhaps the

largest, most elaborate example of this early phase of park design.

In time, the alpen flavour of the Rustic style broadened to include

Tudor, Queen Anne and Chateau style elements. To capitalize on the

interest in wilderness recreation, tourist accommodations were

constructed by railway and park operators. The railways exerted

great influence on early design practice in Canada's National

Parks. Large hotels formed an essential part of this form of

tourism. Largest and best known of the resort hotels within the

parks is the CPR's Banff Springs Hotel (1886) by Bruce Price. The

hotel also has 20th-century additions by William Painter

(1903-14) and J.W. Orrock (1926-28).

As the number of support buildings increased in the parks larger

buildings were required. The structural limitations of traditional

log building methods were solved by using decorative rustic

elements over a substructure of reinforced concrete, a method used

in the Cave and Basin National Historic Site,

Banff. Other commercial buildings in Banff soon followed this

modern method of wood cladding a concrete structure.

Before 1950, a fully developed and consistent Rustic style

became the architectural character of National Parks townsites and

remote parks buildings. Edward Mill's comprehensive report on

Rustic style architecture in Prince Albert National Park describes

the evolution of pre-1948 building stock in four distinct

phases:

- The first phase, from 1927 until 1930, followed soon after the

establishment of the architectural division of the National Parks

Branch, this division was given a mandate to develop distinctive

architectural guidelines for buildings within the national parks

system. A Rustic style was developed to harmonize with the natural

surroundings; native materials and motifs from the Picturesque

cottage tradition were used to express the building's

character.

- The second phase, from 1931-1936, developed with new

architectural guidelines and a need to employ Canadians during the

Great Depression. Labour-intensive building projects that might

otherwise have been regarded as too expensive were built at many

National Parks and National Historic Sites. This situation

encouraged extensive building throughout the ever-growing Parks

Service. An example from this phase is the South Gate Registration, Building 3, at

Waskesiu in Prince Albert National Park. Tudor Rustic in design,

the building is distinguished by the successful use of natural

construction materials.

- The third phase began in 1936 (when relief funding ended and

with it the centralized architectural program in the national

parks) and lasted until 1940, when the Second World War disrupted

construction activity. After the disbanding of the architectural

division in 1937, all design work for the National Parks was

handled by Engineering and Construction Services, a branch of the

newly formed Department of Mines and Resources. After 1937,

economic restraint is seen in the use of milled-frame construction

using manufactured lumber products. The rustic log cabin theme was

interpreted through the use of cheaper log siding applied to the

side of these frame structures.

- During the fourth phase of construction, from 1945 through the

1950s, the rustic effect was achieved mainly through the continued

use of half-log

siding. Labour shortages

and cost restraints meant the pursuit of distinctive rustic

architecture was largely abandoned and stock plans borrowed from

other government building programmes such as the Soldier Settlement

Board and Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

siding. Labour shortages

and cost restraints meant the pursuit of distinctive rustic

architecture was largely abandoned and stock plans borrowed from

other government building programmes such as the Soldier Settlement

Board and Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

By the 1970s there was an increased awareness and appreciation

of early Rustic architecture as many buildings of this style from

the early 20th century were now in need of restoration.

In 1992, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada

recommended for designation as National Historic Sites several

impressive intact Rustic style buildings within the National Parks.

These included: Abbot Pass Refuge Cabin, Banff National Park;

Twin Falls Tea House, Upper Yoho Valley, Yoho

National Park; Prince of Wales Hotel, Waterton Lakes National

Park; Skoki Ski Lodge, Banff National Park; East Gate Registration Complex ,

Norgate Road, Riding Mountain National Park; and the Information Centre (Former

Administration Building), Jasper  Townsite, Jasper National

Park.

Townsite, Jasper National

Park.

Rooted in the Canadian vernacular, the Rustic style has become

firmly established in the Canadian popular imagination. Today, the

Rustic style's hand-hewn wood, robust stones, and a faint fairy

tale charm help us to identify with the establishment of our vast

network of National Parks. So if you decide to visit a National

Park this summer, look for these picturesque buildings, and take a

moment to ponder the distinctive craftsmanship of the Rustic

style.